Gross Indecency

An inside look at documentary theater

Gross Indecency: The Three Trials of Oscar Wilde performs June 13 & 14 at 7:30 PM. Leominster City Hall. Free Admission.

How can theater be documentary? The two mediums seem like opposites, but theatrical devices lend themselves better to documentary reenactments than the realistic style of traditional fiction films. Reenactments attempt to convey the feeling and facts of an event without having the viewer mistake them for the real thing. A documentarian using reenactments often wants to avoid the hyper-realistic style of fiction films, so that viewers are always aware of what is staged and what is real. Documentary plays are created for live theatrical performances, but they use the traditional methodology of documentary, such as real stories, in-depth research, interviews, and direct excerpts from reliable primary sources.

For the past two months I have been working as the stage manager for a production of Gross Indecency: The Three Trials of Oscar Wilde, a documentary play by Moisés Kaufman. The play is being put on by City on a Hill Arts, a company that has mounted a handful of documentary plays such as Seven, co-written by seven female playwrights from around the world; Right Before I Go by Stan Zimmerman; and The Laramie Project by Moisés Kaufman and the Tectonic Theater Project.

The Tectonic Theater Project is known for creating and producing documentary plays. It is led by playwright Moisés Kaufman, whose ensemble has helped construct plays through extensive research, primary source documents, and recorded interviews. Gross Indecency: The Three Trials of Oscar Wilde was their first documentary theater production in 1997. They later went on to assemble two plays from over 200 interviews with residents of Laramie, Wyoming. The Laramie Project and The Laramie Project: Ten Years Later are about the 1998 murder of a young gay man named Matthew Shepard, which was ruled a hate crime.

Gross Indecency begins at the peak of Wilde’s success. Wilde was an Irishman who had risen through English society to become an extremely popular and critically acclaimed writer. In the 1890s, when the trials began, his two plays An Ideal Husband and The Importance of Being Earnest were being performed in London. His novel The Picture of Dorian Gray was already being recognized as a great literary work. But Wilde lost everything when he was brought to trial for having romantic relationships with other men.

What makes it documentary theater as opposed to simply "based on a true story" is that primary source materials are excerpted almost exclusively and also cited throughout. There are no fictionalized scenes. The ensemble narrates and also announces the sources being used for each moment or scene. All the courtroom scenes are edited from the original trial transcripts. Accounts of private and more intimate moments are quoted directly from letters and autobiographies of friends of Oscar Wilde such as Lord Alfred Douglas (Wilde's lover), Frank Harris, George Bernard Shaw, and Sir Edward Clarke (Wilde's lawyer).

To get a more in-depth view of the current production I wanted to interview director Jack Crory about the experience of mounting a documentary play and the value of political theater. This interview has been trimmed and slightly edited for clarity.

SUBJECTIVE OBSERVER: What made you initially interested in directing Gross Indecency?

JACK CRORY: Well, there are a few things that came together at once. One is that I've been involved in The Laramie Project twice. I was interested to read other plays the Tectonic Theater Project had created, and to me Gross Indecency was an even more interesting thing to do within that method of documentary theater. I liked the idea of having a play that's based on real words, but those words are all from the past. It's a bit more distant - all from transcripts of trials, from letters mostly, so that was interesting to me that you could construct a very dramatic play, but not write any dramatic scenes. To just pull from all real sources.

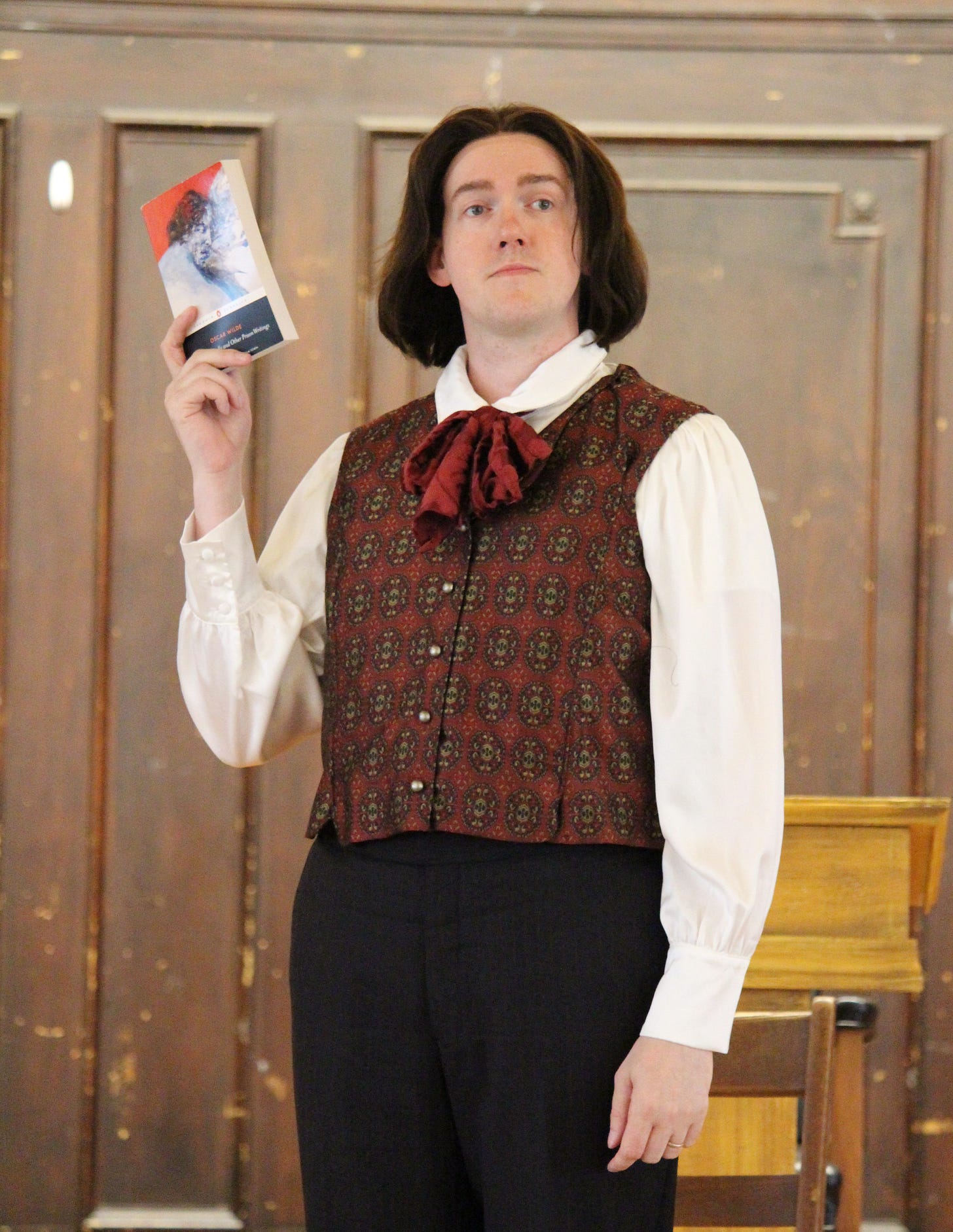

I'm also very interested in Oscar Wilde as an author and a thinker. Whenever I circle back to Oscar Wilde, and read something new by him, I'm struck by the profound insights that he has about the nature of truth and how we construct our identities. And I think that this play really gets at some of his ideas while at the same time just telling the story of this obviously pivotal moment in his life. And I will say also that I wanted to direct this play because I'm involved with this company, City on a Hill Arts, and another person another artist who is very involved in this company is David Allen Prescott. I thought that they would be an excellent cast for the role of Oscar Wilde, so I just thought it would be a perfect marriage between an actor and material.

SO: How is the experience working on documentary theater projects like Right Before I Go, The Laramie Project, and Gross Indecency different from working on traditional fiction plays?

CRORY: Well, I can talk first about acting in The Laramie Project and Right Before I Go. What I've come to appreciate working on those two plays as an actor is that an actor delivering a monologue on stage to an audience can be spontaneous and unpredictable and can have its own special charge of energy that is not present in film or TV. It became a special experience, because I knew they were based on the people's real words.

As far as directing Gross Indecency, it’s different from directing other plays because I'm not so much thinking about how an author has crafted a story line, but I'm thinking more about actual events that happened, things that real people said, and I'm thinking about what we're doing as simply interpreting how the playwright Moisés Kaufman has selectively edited those words. You know, typically when rehearsing a play there are many discussions with actors about why a scene is written the way that it is. Why is this here at this point in the play? But the discussions in Gross Indecency were completely different. It’s more about, “okay, why was this part of the transcript selected and not this other part? Why is this text from something Oscar Wilde wrote being juxtaposed with something from a trial?” There's also a lot of talk with actors about, you know, all of the real people who they are portraying.

The last thing I would say is that Moisés Kaufman instructs a company to perform the play in a Brechtian style—the actors are really not supposed to inhabit the roles in a realistic way. In other words, they're not supposed to ask the audience to suspend their disbelief, and act like they're not aware that they're looking at actors on a stage. Instead you're supposed to present it to an audience in a way that they're always aware of the actors. That's a style that I feel just goes hand-in-hand with the whole idea of documentary theater.

SO: Why do you think it's important for people to experience Brechtian theater? As we you were saying, plays which tear down the fourth wall and realism.

CRORY: As Moisés Kaufman and other members of the Tectonic Theater Company and Brecht make clear in their writings, when you think of realism as the default or main way to tell a story, you're really just leaving by the wayside so many other possibilities for storytelling and the creation of art. To me it’s about freeing up artists to explore all the different ways that stories can be told by kind of discarding realism. Another thing that Brecht was really big on, at least at one point in his career, was this idea that theater should be more focused on being thought-provoking and intellectual than emotion-inducing. There’s a lot of discussion about Brecht, about how much he truly believed that - how far you can really take that? But I do find the general insight valuable.

In this production of Gross Indecency I'm trying to follow in the Brechtian tradition by having, you know, simple theatrical devices that are alienating and cause people to think about the story they're watching, but not necessarily get lost in it [like you would with] a realistic story. For example, there's a section in which there are many lines from Oscar Wilde's third trial in the script and we get different snippets that are all kind of placed one after another, of things that were said during the trial, rather than an extended back and forth sequence of questioning like from the first two trials. We have the actor playing Oscar Wilde just sort of moving about the stage, not sitting in a chair or standing at a bar like he would have been in the actual trial. We have actors standing up shouting out their lines from different places in the room. And while all this is going on, someone is beating a frame drum, which is meant to suggest in a theatrical way a heartbeat, or the mental pressure that Oscar Wilde was feeling as all this was bearing down on him. So all those things, like having people move about the space in a non-realistic way, and the drum—those are meant to just get people thinking about how Oscar Wilde may have felt during that trial, and those devices are only possible if you abandon realism.

SO: Why do you think Moisés Kaufman and others choose theater as opposed to film, which people traditionally associate with documentary? Why choose theater for the documentary form as opposed to film?

CRORY: There are many elements of artistic communication that theater has that film does not have. You know, in a theater everyone in an audience is in a space and they are they are in relation to all the other things that are in that space - what's on stage and the other audience members. When someone's watching a film, whether that's in a cinema or on television, they are just looking at a screen. But in a theater you are you are literally in a space and there's all sorts of meanings that can come from where things are placed...

It's really part of the culture of theater that plays are performed over and over again with different actors and seen at different times and places. So when a playwright creates a play either by writing their own or by assembling, you know, material into a play like Moisés Kaufman does here, he is not just creating one theater production - he's creating a blueprint for many productions to happen in the future in times and places that he cannot imagine. So there's something very powerful about participating in theater, whether as an artist or as a spectator, because you know that you are watching or performing something that has been performed by people before you and will be performed afterward.

SO: Moisés Kaufman published a letter opposing the recent cuts to the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA). What role can this play and other works of art have in this current political moment?

CRORY: I don't think that any one theater production on its own can change the political trajectory of the United States, because by its nature, it's not a mass medium. Only so many people can be in a room at a time to see a play. However, I think that if people all over the United States are involved in artistic and literary activities that challenge bigotry, that challenge abuse of power, that challenge the ideas behind authoritarianism, then eventually everyone in America will have the chance to see that people in their communities do not see authoritarian government or some of the bigotry behind the MAGA movement as normal or good.

Like Leominster is a small city in the middle of New England. It's in Massachusetts. People think of Massachusetts as a very liberal or progressive state, but those of us who are in Central Massachusetts know that, you know, it's a very different culture than the Boston area. But I feel that if there were a production of Gross Indecency, or a similar play, or other artistic events like it that were happening in cities like Leominster all over the country, every month of the year for the next four years, then I think that it would make a—not in achieving a certain outcome, but in creating a culture in which people just reject authoritarianism. They reject fascism. They reject the idea that the things that they should be looking for in leaders are those who find scapegoats and blame them for their problems.

If people were going to see stories in which they're reminded about all of our flaws and how we can overcome them as human beings, then I think gradually over time that leads to a better society. So, I'm just a big believer in arts, culture, and education being something that can permeate a democracy. And that will allow people to find their better selves and develop ideas. That will then bubble up through our elections into choosing better leaders.

What Moisés Kaufman was referring to specifically in his letter was the cutting of arts funding. He was writing that letter in response to cutting funding for the NEA and other things. It was the Trump administration's way of trying to stifle the type of arts and culture that I'm talking about. Moisés Kaufman is very aware that authoritarians are aware that organic grassroots arts, tolerant arts and culture are bad for their aims. And so that's why they're trying to choke it off with funding. That’s why it should be resisted.