A Tragic Love of Cinema

Close-up and Close-up Long Shot

For many cinephiles, Close-up is in the pantheon of the all-time greatest films. This Iranian film, released in 1990, propelled director Abbas Kiarostami to international fame. It is known for blending fiction and nonfiction, and there have been heated debates about whether it should be categorized as fiction or documentary.1

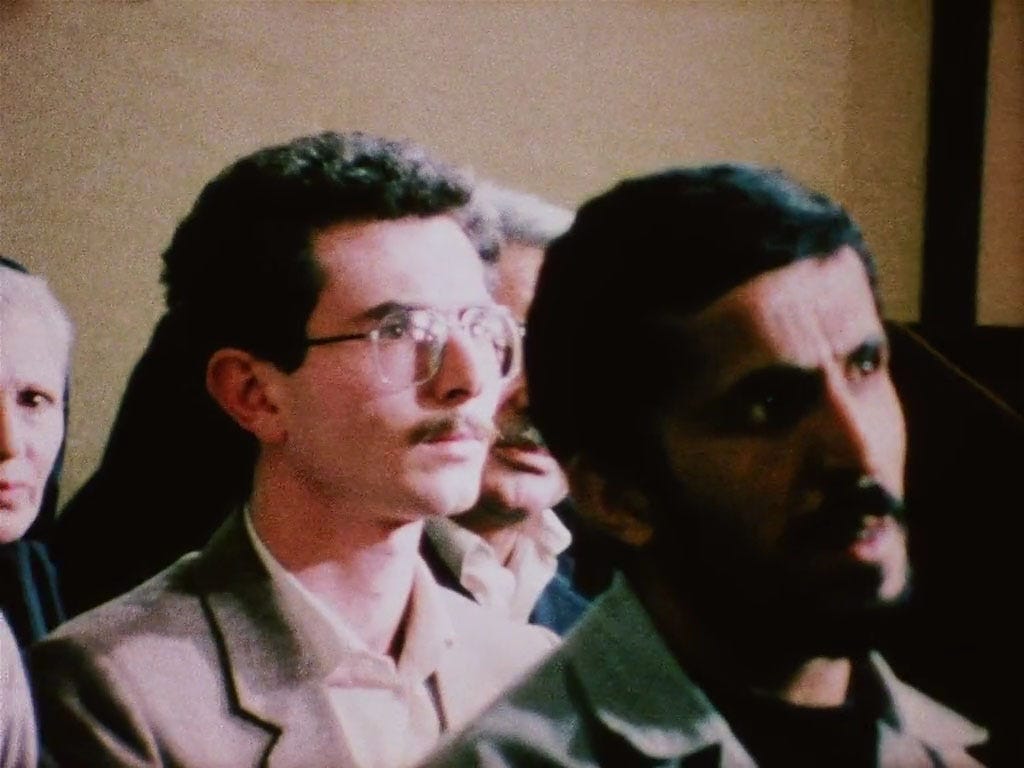

The main protagonist is Hossein Sabzian, a poor bookbinder with a passion for cinema. Sabzian befriends the middle-class Ahankhah family by convincing them he is the famous Iranian director Mohsen Makhmalbaf. Sabzian starts making plans to cast the family in a movie he wants to shoot. Eventually the family discovers Sabzian’s fraud, and he is arrested and brought to trial. During his trial Sabzian tries to explain his actions and how his dream of becoming a director led him to deceive the family.

If this were a purely fictional film, then it would be easy to enjoy the story and appreciate all the rich details and nuance. Despite his act of deception, Sabzian is portrayed as a sensitive, intelligent, and sympathetic person. There is a moving climax and conclusion at the end of the film. The credits roll with Sabzian smiling as he clutches red flowers. It is hard not to be affected by the beauty and tenderness of these cinematic moments.

But the story of Sabzian’s life and the filmmaking process were much more complicated than a traditional narrative film. Most of what is seen on screen is either reenactments of past real events or observational footage of real events. But Kiarostami makes no effort within the film to explain to the viewer what was real, what was scripted, and what events he directly influenced for the sake of his film. Because of extensive research and interviews with Kiarostami, viewers today are now able to understand more clearly which elements were reenactments and which real-time events Kiarostami shaped.

Kiarostami worked closely with Sabzian to script his defense before the trial. The trial was recorded as it happened, and it is extraordinary that Kiarostami was allowed to do so. The mullah serving as the judge had great leeway in how to operate his own courtroom, and he decided to give Kiarostami permission to film. The most shocking revelation about the process is that Kiarostami made great efforts to convince the judge to rule in Sabzian’s favor. (The director’s heavy-handed role behind the scenes is not part of the film.) Both the family and Sabzian were unhappy about Kiarostami’s meddling in this way. This approach raises several ethical red flags, but some directors feel that is the price of great cinema. How could the film be impactful without Sabzian’s impassioned pleas? What if he were sentenced to prison? Kiarostami argues that he was helping Sabzian and fulfilling both parties’ desires to have their side of the story told. He claims they could have refused to participate, which was a constant fear he had during the filmmaking process.2

Another problem with this hybrid approach is that it can lead to thinking of real people as characters outside our reality. In a 2009 interview for Criterion, Kiarostami compared Sabzian to a character from a Dostoevsky novel. That’s not usually a compliment. Many of Dostoevsky’s characters suffer through poverty, intense psychological distress, and crippling existential questions.3 When Kiarostami spoke about his challenges working with Sabzian, he recounted his own anxieties and Sabzian’s distrust of him. He spoke as if he were dealing with a difficult actor, and not someone who had a lot to lose if he was portrayed negatively. Kiarostami does show genuine respect for Sabzian’s intelligence and love of film, but it is clear he saw his subject closer to a literary character than a real person.4

The stark contrast between Close-up and Sabzian’s lived reality is most evident in the 1996 documentary Close-up Long Shot, directed by Mahmoud Chokrollahi and Moslem Mansouri. This 40-minute documentary came out six years after Close-up. It is about Sabzian’s life in his hometown, Isfahan, where he still works at the same bookbinding business and lives in poverty. It is simple in its approach– mainly long interview takes with Sabzian and short segments of b-roll. Sabzian’s neighbors have all seen Close-up, and instead of seeing him as a thoughtful and sympathetic figure, they see him as a conman or a lunatic. His boss says he thinks Sabzian is insane for his obsession with cinema. Sabzian’s sister is almost in tears as she explains that he is forever stained as a criminal for participating in Close-up. We learn that Sabzian’s passion for moviegoing began when he was just a young child. There is also a harrowing story from his childhood that reveals the immense difficulties he has faced throughout life. The starkness of Sabzian’s life as captured in Close-up Long Shot in contrast to the beauty of Close-up is unsettling and haunting. It could be argued Close-up is not complete without this illuminating follow-up.

There seems to be broad agreement between Sabzian’s neighbors and Kiarostami that Sabzian had a fatal love of cinema. Even Sabzian himself expresses regret that his passion has led to hardship and suffering. But I would argue that this viewpoint misses the greater and more devastating tragedy of Sabzian’s life: the poverty that makes it impossible for him to find meaning and fulfillment.

What if Sabzian had been born into a middle-class family? What if he had the opportunity to attend a university and make connections the way Kiarostami did? In Close-up Long Shot Sabzian laments that the directions Kiarostami gave during filmmaking were extremely similar to Sabzian’s directions when he tried to make a film with the Ahankhah family initially. His neighbors and Kiarostami talk of Sabzian’s devotion to cinema as an unhealthy obsession, but many well-known directors speak about their early love of cinema, their giant film collections, and their never-ending study of the art form. In Sabzian’s case it is viewed as a psychological disorder, but for an accomplished director it would be seen as proof of his genius and dedication.

The critiques against Sabzian have often been used cruelly against artists who live in poverty or encounter frequent financial struggles. Those who pursue college degrees in the arts are judged as “wasting” their education. Their financial difficulties later on are seen as rightful punishment for bad choices. Artists who don’t or can’t pursue formal education are often labeled amateurs if they try to break into the professional world, even if they have extensive experience. The illusion of a world of meritocracy still exists, and few want to admit that success in the film industry is often dependent on money and connections. Sabzian did not even have the chance to get any training or to pursue filmmaking professionally. In this sense, Sabzian has several similarities to a different working-class filmmaker I have written about on this Substack, Mark Borchardt, who is the main participant in American Movie. Borchardt is portrayed in a more comedic way than Sabzian, but both have a passion for film that is stifled by their social class and sometimes ridiculed by their peers.

Often I wonder how Sabzian’s life might have been different had he been born later – what if he were a young man with his same passions now? I don’t think that Close-up could be made today because of social media and the general awareness of marketed online personas. I think Sabzian’s “obsession” would probably be more broadly accepted amongst the thousands of online film forums and fan groups. Perhaps he would be the moderator of the Makhmalbaf Reddit page and have a Tiktok in which he reviewed films. Or maybe he would prefer to have a thoughtful blog about film.

Sabzian died at the age of 52 of a heart attack in 2006, but he still has an intense following online. There are several online forums in which he is continually discussed. There is an international film journal, Sabzian, named in his honor. Sabzian’s devotion to the art of film is what has given Close-up lasting resonance. The tragedy of his life was not that cinema ruined him, but that he never had the opportunity to pursue his dreams.

***

Close-up is available to stream online for free on Kanopy in the United States and Canada through your university or public library.

Close-up Long Shot and the 2009 interview with Kiarostami are available to watch on DVD or online through the Criterion Channel.

The most precise way to describe Close-up is as a hybrid. Contemporary filmmakers have increasing begun to describe a film as a hybrid if it relies heavily on both documentary and fiction elements. This is fairly new term that wasn’t being widely used when Close-up first came out.

Abbas Kiarostami on Close-up, 2009 Interview conducted for the Criterion Collection.

Fyodor Dostoevsky (1821 – 1881) was a Russian writer known for portraying the hardships and existential struggles of ordinary people. He often used his own life, family, and friends in his fiction. His novel House of the Dead is a loosely fictionalized account of his four years in a Siberian prison.

Abbas Kiarostami on Close-up, 2009.